Writing a Language in Truffle. Part 2: Using Truffle and Graal

I was hoping to get this next installment out earlier. Sorry for the delay. Now after Thanksgiving, a vacation and a bout of the flu I’m ready to get back into it.

Last time I created a simple interpreter for a lisp language I called Mumbler. This time around let’s actually use Truffle and Graal to run our interpreter. We’ll start off with the minimal amount of Truffle we need to get our interpreter to compile and run. If the bare-bones interpreter isn’t fast enough we’ll investigate more Truffle hooks to speed things up.

Table of Contents

- A Truffle Crash Course

- Conversion Plan

- Extend

NodeClass - Declare Mumbler Types

- Create

execute<Type>methods inMumblerNode - Add Nodes For Literal Data Types

- Node To Read Variables

- Function Invocation

- Implement Mumbler’s Special Forms

- Add Builtin Methods

- Update

Readerto Return New Truffle Nodes - Updating Main Class

- Benchmarks

- What’s (Maybe) Next

A Truffle Crash Course

I mentioned previously how Oracle Labs has released an experimental Java Virtual Machine (JVM) that contains a new Just in Time (JIT) compiler called Graal. Graal was designed to improve the speed of dynamic programs. Much like how the HotSpot VM speeds up Java bytecode Graal is meant so speed up code written in Java. To use Graal you need to use new built-in APIs to get access to the runtime and annotate your codebase so Graal has more type information at runtime. These APIs are called Truffle. Through the course of this post we’ll go into more detail about the Truffle APIs but for now we’ll just say that Graal is the JVM runtime and Truffle is the API we call and use to annotate our Java code.

Installing Graal & Truffle

The easiest way to get Graal is to download the preview VM Oracle Labs provides. You can add this VM to Eclipse or any other IDE and build against it.

I’m using a snapshot from their Mercurial repo. I don’t think my code will compile against the preview version anymore. No problem. You can clone the repo and build it pretty easily. I did all this in Linux but they have instructions for Mac OS X as well. For Windows… you may want to get a VM like VirtualBox and a Linux distro to try this out.

You can follow the instructions on the Truffle OpenJDK wiki on how to download, build and install Truffle. You’ll need to have both Java 7 and Java 8 installed on your system. As a quick recipe you can do:

$ hg clone http://hg.openjdk.java.net/graal/graal

$ cd graal

$ echo -n "JAVA_HOME=<path-to-java-8>\nEXTRA_JAVA_HOMES=<path-to-java-7>" >> ./mx/env

$ mx --vm server --vmbuild product buildNow you have the latest version of Truffle and Graal. The freshly built VM is in the jdk_1.8.<version-number> directory.

To get the code to work in Eclipse you’ll need to do a few more steps. Again, the Truffle team has a wiki page on Eclipse. The steps are little more involved so I recommend you read through their instructions.

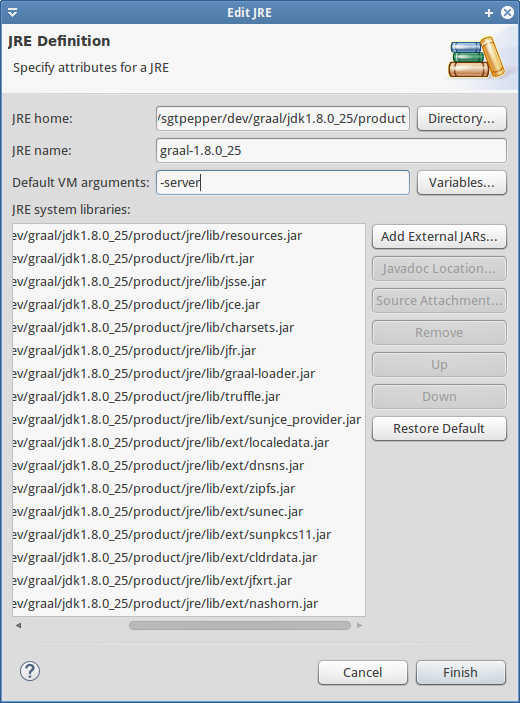

I had a little trouble installing the VM in Eclipse when following their instructions. The Graal jar files weren’t automatically included. If you click “Add External JARs…” and try to match the list I have pictured here it should work for you too.

The list of JARs needed for Graal VM

I don’t think the wiki page mentions this but you’ll need to enabled annotation processing on your Eclipse project. Go to Properties -> Java Compiler -> Annotation Processing and select Enable annotation processing. Then go to Properties -> Java Compiler -> Annotation Processing -> Factory Path click Add External JARs... and add the Truffle jar. It will be under $graal_location/build/truffle-dsl-processor.jar. I don’t think the preview download includes the jar.

Conversion Plan

Since we already have a working codebase we’ll take that code and migrate it over to use Truffle. Truffle has some classes that we must use to take advantage of Graal’s compiler. Truffle also assumes a certain structure to an interpreter that differs from what we did in our simple Mumbler interpreter. Below are the big architectural changes we need to make to get our interpreter to compile and run on Graal.

-

Extend

NodeclassTruffle has a baseclass called

Nodethat must be extended by all nodes in our AST. This shouldn’t be too difficult since we already have a base class calledNodein our simple interpreter. -

Declare Mumbler data types

One of the big strategies Graal uses to get speed-ups is to use type information. To accomplish this we need to let Graal know what the types our language uses through Truffle annotations.

-

Create

execute<Type>methods inMumblerNodeWith our newly created types we need to provide

evalmethods (customarily calledexecutein Truffle) for all our Mumbler types. Truffle will do the heavy lifting of calling the specialized method for the right type. -

Add nodes for literal data types

We’ll start creating simple Truffle nodes that don’t do much. They just return a constant value. We’ll need a node for each of our builtin types.

-

Add node to read variables

Truffle includes classes for storing and retrieving variable values. We’ll replace our simple environment classes with Truffle’s

Frameclasses to create lexical scoping. This includes variable lookup going up the lexical scope stack, writing variable values in the current scope and creating new scopes when a new function (lambda) is called. -

Function invocation

Finding and calling (invoking) a function requires instantiating some special Truffle classes. Though a little complicated the code is thankfully well modularized so there isn’t much accidental complexity.

-

Implement Mumbler’s special forms

At this point we can read variables and call functions. We’ll round out the functionality by implementing Mumbler’s four special forms (

define,lambda,if,quote). After this step we can now define new variable and create new functions plus have control flows. -

Add builtin methods

Our language now has all the features it needs but still needs some basic functions like arithmetic and list functions.

-

Update

Readerto return new Truffle nodes.We have all the parts in place now we just need to update

Readerto take anInputStreamand return our new AST structure. - Update main class

Now that we have a plan on how we’re going to go from our custom interpreter to a Truffle-based interpreter let’s get started!

Extend Node Class

This step is pretty straightforward. We already have an abstract base Node class in our interpreter. It should be a simple step of having our class extend Truffle’s Node class. I’m renaming our class to MumblerNode to make it easily distinguishable from Truffle’s Node class. That should do it.

While we’re at it, we’ll also annotate our base class with Truffle’s NodeInfo annotation. NodeInfo is a way to provide some info about our nodes we can use when debugging. With that we’re done with this step.

Here’s how our MumblerNode looks at the moment:

1 2 3 |

@NodeInfo(language = "Mumbler Language", description = "The abstract base node for all expressions") public abstract class MumblerNode extends Node { } |

Declare Mumbler Types

Now we need Truffle to declare the builtin data types for Mumbler. If you go back to the previous post we conveniently listed out all the data types available in Mumbler. We have Number, Boolean, Symbol, Function and List. Number and Boolean are equivalent to Java’s long and boolean primitive types, respectively, so we’ll use those so we can eliminate boxing/unboxing. The rest of the types aren’t built into Java so we’ll create our own classes. We can copy over our implementations from our simple interpreter minus the eval method since the these classes will stay pure data structures in our Truffle version. We’ll prefix our class names with “Mumbler” again to make associations explicit. MumblerFunction and MumblerSymbol are very simple.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 |

public class MumblerFunction { public final RootCallTarget callTarget; private MaterializedFrame lexicalScope; public MumblerFunction(RootCallTarget callTarget) { this.callTarget = callTarget; } public MaterializedFrame getLexicalScope() { return this.lexicalScope; } public void setLexicalScope(MaterializedFrame lexicalScope) { this.lexicalScope = lexicalScope; } } |

RootCallTarget is a Truffle’s class that encapsulates a function. We’ll go into more detail when we implement lambda.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 |

public class MumblerSymbol { public final String name; public MumblerSymbol(String name) { this.name = name; } @Override public String toString() { return "'" + this.name; } } |

MumblerSymbol is even simpler. We just store the name of the symbol and that’s it. We override toString to help when debugging. I’m going to override toString for most of the nodes as well to help with debugging though I’m going to omit that code here. You can see the whole code on GitHub.

MumblerList is a little more complex since it implements a linked list, but we already wrote a version in our simple interpreter. We’ll just reuse that code. Refer to the previous post or check out the git repo.

Now that we have all our builtin data types we have to create a special class to let Truffle know about them.

1 2 3 4 |

@TypeSystem({long.class, boolean.class, MumblerFunction.class, MumblerSymbol.class, MumblerList.class}) public abstract class MumblerTypes { } |

The important piece is the annotation we add to our class. This lists out all our types. Keep in mind that order matters. Graal will go down the list in order and return the first datatype that succeeds. So, for example, if we had arbitrarily long numbers using BigInteger we want to make sure that comes after long or else BigInteger would be tried first and always return. We would never get the benefits of primitive types for smaller numbers.

In more complex languages the class could contain methods to handle conversion between one type to another. If we utilized BigInteger like I mentioned we could have a cast method to convert long to BigInteger. We could also specify our own type checks to check if a given Object is a certain type. We would use this if we had a null type, but since we’re using an empty list as null we’re not going to implement that.

Create execute<Type> methods in MumblerNode

Now that we have our root node and our types defined we can start implementing the various execute methods. Unlike our simple interpreter we’ll need a special execute method for each datatype we declared in MumblerTypes so Graal can use the right one at runtime to get the fastest speed possible. We still need the catch-all method that can return a generic object in case all other methods fail. We’ll put these in our root node class MumblerNode.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 |

public abstract class MumblerNode extends Node { public abstract Object execute(VirtualFrame virtualFrame); public long executeLong(VirtualFrame virtualFrame) throws UnexpectedResultException { return MumblerTypesGen.MUMBLERTYPES.expectLong( this.execute(virtualFrame)); } public boolean executeBoolean(VirtualFrame virtualFrame) throws UnexpectedResultException { return MumblerTypesGen.MUMBLERTYPES.expectBoolean( this.execute(virtualFrame)); } public MumblerSymbol executeMumblerSymbol(VirtualFrame virtualFrame) throws UnexpectedResultException { return MumblerTypesGen.MUMBLERTYPES.expectMumblerSymbol( this.execute(virtualFrame)); } public MumblerFunction executeMumblerFunction(VirtualFrame virtualFrame) throws UnexpectedResultException { return MumblerTypesGen.MUMBLERTYPES.expectMumblerFunction( this.execute(virtualFrame)); } public MumblerList<?> executeMumblerList(VirtualFrame virtualFrame) throws UnexpectedResultException { return MumblerTypesGen.MUMBLERTYPES.expectMumblerList( this.execute(virtualFrame)); } } |

As you can see, the methods are all the same with only a change in which expect method is called. I’ll explain executeLong and you can infer the rest. Basically, we call the generic execute method to get a response. We then call the expectLong method from MumblerTypesGen.MUMBLERTYPES (which was generated from our MumblerTypes class) to verify the type is indeed a long. If the type is correct we return and Graal makes a note that this execution returned a long type. If the type is incorrect an UnexpectedResultException is thrown.

Usually, up the execution chain the exception is caught and the call to executeLong is dropped. The next type listed in MumblerTypes is tried. In this case, executeBoolean is called and if that throws another UnexpectedResultException then executeMumblerSymbol is called and so on. Sometimes we want an explicity type. For example, when we are making a function call we want to be sure the first element in the list evaluates to a function so we directly call executeMumblerFunction. If that throws an UnexpectedResultException then we know we have a problem and have to deal with it. Either way, these methods ensure we get the type we expected.

The VirtualFrame argument in all the execute methods gives you access to the function’s namespace and its arguments, but we don’t need that right now. That’ll come handy when we start trying to read/write variables and function parameters.

You’ll notice we haven’t actually implemented any execution logic. We just assume there’s an execute method implemented somewhere and call that. Our yet-to-be-written concrete subclasses will have to implement generic execute methods. The subclasses also override any of the type-specific execute methods if there’s a faster way to run than the strategy used for all types.

Add Nodes For Literal Data Types

Time to create some concrete nodes. We’ll start off with simple classes that return a constant value. In Mumbler, whenever you see numbers, boolean literals or symbols/lists in a quote special form we want to return those specific values. We’ll need MumblerNode subclasses for each of these types. Here’s the node class for a literal number.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 |

public class NumberNode extends MumblerNode { public final long number; public NumberNode(long number) { this.number = number; } @Override public long executeLong(VirtualFrame virtualFrame) { return this.number; } @Override public Object execute(VirtualFrame virtualFrame) { return this.number; } @Override public String toString() { return "" + this.number; } } |

There shouldn’t be anything too surprising. NumberNode extends MumblerNode and therefore has to override execute. We return the number provided when this node was created. Since execute returns an object there will be boxing involved which we want to avoid. To do this we also override the executeLong method which returns a primitive long type. Since our number is already a long we can just return it and call it a day. We also implement toString for debugging purposes.

Here’s the symbol node class as another example.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 |

public class LiteralSymbolNode extends MumblerNode { public final MumblerSymbol symbol; public LiteralSymbolNode(MumblerSymbol symbol) { this.symbol = symbol; } @Override public MumblerSymbol executeMumblerSymbol(VirtualFrame virtualFrame) { return this.symbol; } @Override public Object execute(VirtualFrame virtualFrame) { return this.symbol; } @Override public String toString() { return this.symbol.toString(); } } |

The layout is almost exactly the same as NumberNode. We just change the types to MumblerSymbol such as overriding executeMumblerSymbol instead of executeLong.

We’ll skip passed boolean and MumblerList literal nodes since they are essentially the same, but you get the idea of how to create nodes in Truffle. Is is very similar to how we did it in our simple interpreter but requires a little bit more work when you want a faster implementation of an execute method. Thankfully the amount of additional work is very small and doesn’t complicate our code.

If you noticed, we’re not creating a literal node for functions even though it’s one of our basic data types. That’s because returning functions is done through lambda and has no other way of returning functions. We’ll tackle lambda later when we implement all special forms.

Node To Read Variables

Now that we have the basics of Truffle node creation under our belts let’s try something with a little more meat on it. We’ll implement the node that reads variables and returns the value. If you remember from our Mumbler spec, when symbols are evaluated they return the value mapped to the symbol’s name. If one doesn’t exist in the current namespace we look at the surrounding lexical scopes or throw an error if the variable cannot be found.

Truffle Frames

Before we start coding let’s talk about Truffle’s Frame classes. Frame is Truffle’s interface to store/read data in the current namespace. When a function is called a new Frame is created, but you can also create new ones yourself if you want to implement something like block scope that is in C-like languages like Java. Mumbler creates a new scope at the function level so we don’t need to worry about creating new frames in other situations.

There are two implementations of the Frame interface. The more common one is VirtualFrame which we’ve already seen in our execute methods. This is the more lightweight frame that is preferred because Graal can easily optimize it when you’re not using frames; Graal can also merge multiple virtual frames into one. The second kind is MaterializedFrame. This frame is stored in heap memory so it can be accessible from different functions. These frames can live beyond the scope of the function where they were created and is a must for lexical scope. What you gain in power and flexibility you lose in speed and memory size. Graal cannot optimize this version as well so you take a hit by using them.

Like most things in Truffle we need to be aware of types while we’re executing to make sure we don’t do unnecessary boxing of primitives. Frames keep track of the type within the key we use to set and get our values. Instead of using strings directly (like we did in the simple interpreter) Truffle has a custom type called a FrameSlot. The two main pieces of metadata we need to concern ourselves with are the identifier and the and the FrameSlotKind. The identifier is the real key the frames use to set and get values. Though it can be any object we’ll stick with strings that are the variable names. The FrameSlotKind piece stores the type that is stored by this FrameSlot instance. FrameSlotKind is an enum that contains all of Java’s primitive types plus one for objects and an Illegal value if we don’t know the type yet.

So the two things to keep in mind when using Truffle frames is we need to use FrameSlot instances as keys and the FrameSlotKind value needs to be set properly so Graal can properly optimize our code. Once we know that the kind is set properly we can call optimized methods like getLong on our frame object, but only if the kind is set properly. If we call getLong and it’s not a long an exception is thrown.

Implementing Lexical Scope

Truffle frames are a flat map. Also, they don’t live beyond the life of the function unless you explicitly make it. This is another way Truffle tries to speed up your code. If you’re not using frames or several frames can be merged into one then why waste all the resources by creating unncessary frames? Unfortunately, for Mumbler we’ll need to have frames longer than the execution of the function so variables can be fetched in the future. The question is how to implement this.

The strategy I’m going to use is pass the lexical scope (an instance of the MaterializedFrame class) around as the first argument to function calls. We’ll check the current VirtualFrame instance for a variable (i.e., the FrameSlot), but if a value isn’t found we’ll look through the lexical scope which is kept in the first position of our arguments array. This way it’s simple to daisy chain frames: we’ll check a frame and if the variable doesn’t exist we’ll look at the first argument and repeat the process.

We have to make sure to properly chain frames when we start a function, but we’ll deal with that when we implement the lambda special form and function invocation. For now we’ll assume the chain exists and is set properly by other components.

Generic Read Method

Let’s take our first stab at writing SymbolNode that reads from the current VirtualFrame and maybe from the lexical scope.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 |

public class SymbolNode extends MumblerNode { public final FrameSlot slot; public SymbolNode(FrameSlot slot) { this.slot = slot; } @Override public Object execute(VirtualFrame virtualFrame) { Frame frame = virtualFrame; Object value = frame.getValue(this.slot); while (value == null) { frame = this.getLexicalScope(frame); if (frame == null) { throw new RuntimeException("Unknown variable: " + this.slot.getIdentifier()); } value = frame.getValue(this.slot); } return value; } private Frame getLexicalScope(Frame frame) { return (Frame) frame.getArguments()[0]; } } |

That wasn’t so bad. The constructor takes a FrameSlot and stores it. We won’t worry about where the FrameSlot instance comes from right now. We’ll deal with that when we migrate the Reader class. The execute method is a little complicated because we traverse our chain of frames to look through all scopes for the value. We call a new method getLexicalScope which fetches the lexical scope from the first element of the arguments list.

So this will technically work, but as you’ve probably guessed it’s slow for primitive types. We need to take advantage of FrameSlot type information to remove boxing. We need to create versions to get long and boolean values. We need to create a version that will always fetch actual objects.

So we can just write versions of executeLong, executeLong, etc and call it a day, right? Not quite. The problem is at compile time we don’t know what type is stored in a given variable. We would need to resort to an if/else chain until we find the right one, but we can’t do that on every read or else variable reads will always be slow. We need to way to try different types one time but later reads immediately skip to the correct method. Truffle gives us a way to do that: tree rewriting. We can do our if/else checks and then we can change our AST at runtime to use the specialized node. If at any time the type changes and what used to be a long is something new we need to rewrite the AST again to revert to the old way. Though we can write a version of this it will be tedious and error prone. Thankfully, Truffle helps us out here again.

Specialized Read Methods

Truffle comes with a DSL (domain specific language) that will write all this boilerplate for us. We just write our specialized read methods, and Truffle will generate specialized nodes for every specialized method we specify. Let’s create 3 specialized methods for long, boolean and real objects.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 |

@NodeField(name = "slot", type = FrameSlot.class) public abstract class SymbolNode extends MumblerNode { public abstract FrameSlot getSlot(); public static interface FrameGet<T> { public T get(Frame frame, FrameSlot slot) throws FrameSlotTypeException; } public <T> T readUpStack(FrameGet<T> getter, Frame frame) throws FrameSlotTypeException { T value = getter.get(frame, this.getSlot()); while (value == null) { frame = this.getLexicalScope(frame); if (frame == null) { throw new RuntimeException("Unknown variable: " + this.getSlot().getIdentifier()); } value = getter.get(frame, this.getSlot()); } return value; } @Specialization(rewriteOn = FrameSlotTypeException.class) protected long readLong(VirtualFrame virtualFrame) throws FrameSlotTypeException { return this.readUpStack(Frame::getLong, virtualFrame); } @Specialization(rewriteOn = FrameSlotTypeException.class) protected boolean readBoolean(VirtualFrame virtualFrame) throws FrameSlotTypeException { return this.readUpStack(Frame::getBoolean, virtualFrame); } @Specialization(rewriteOn = FrameSlotTypeException.class) protected Object readObject(VirtualFrame virtualFrame) throws FrameSlotTypeException { return this.readUpStack(Frame::getObject, virtualFrame); } @Specialization(contains = {"readLong", "readBoolean", "readObject"}) protected Object read(VirtualFrame virtualFrame) { try { return this.readUpStack(Frame::getValue, virtualFrame); } catch (FrameSlotTypeException e) { // FrameSlotTypeException not thrown } return null; } protected Frame getLexicalScope(Frame frame) { return (Frame) frame.getArguments()[0]; } } |

Our SymbolNode class has gotten significantly longer, but there’s nothing too complicated. We’ll go top to bottom. The first thing you notice is a new annotation @NodeField. Instead of creating a FrameSlot field and a simple constructor we now let Truffle’s DSL do the work for us. We define the name of the field ("slot") and it’s type (FrameSlot.class). We create an abstract getter for our slot and Truffle will automatically implement it for us in the generated classes.

Since we need to look up the scope chain in every one of our specialized methods I extracted out the lookup logic into a separate method I called readUpStack. It takes a custom interface FrameGet<T> as its first argument. This interface is actually a Java 8 functional interface, and we’ll use Java 8’s handy new method reference feature to pass in the proper get<Type> method in our specialized methods. How I love first order

functions methods.

With our functional interface and general readUpStack method defined we can now write our specialized functions. The DSL requires the type specialized methods to appear before the generic one so we start with the long method. We annotate it with @Specialization so Truffle knows it a specialized method of a generic method. The rewriteOn value informs the DSL that if a FrameSlotTypeException (if the value isn’t a long) is thrown we throw away our specialized node and revert back to the generic one. We don’t have to write any rollback code or custom tree rewriting code; the Truffle DSL takes care of all that for us. We now repeat the process again for boolean and Object with the only difference being the return value and the object method we pass to readUpStack. Did I mention how much I like first order functions?

We finish up our specialized methods with the generic read method. We still annotate it with @Specialization but this time we define the contains value instead of rewriteOn. contains is how we list our specialized methods. Since method references aren’t supported in annotations (boo) we define them with strings. We still just call readUpStack but we have to catch the checked exception FrameSlotTypeException. The method getValue doesn’t throw a FrameSlotTypeException exception so we just wrap it in a try/catch block and forget about it.

We still have our getLexicalScope method around.

You may notice that our methods aren’t called execute this time. They all start with read. Where are the execute methods? Basically, Truffle writes the execute methods for us. Since the execute methods have to worry about trying the different specialized methods, do a tree rewrite when it finds a correct result, and rollback a rewrite when an exception is thrown there is more to do in execute than we want to bother ourselves with. We therefore write differently named methods, properly annotate them with @Specialization and Truffle will know how to properly tie everything together when it generates our concrete classes. All we have have to focus on is writing our specialized read methods.

So how do we use this concrete class? Truffle will generate a new class called SymbolNodeFactory which will contain a create method. It takes one argument: a FrameSlot and will return an instance of SymbolNode. Initially, the object will be an instance of SymbolUninitializedNode. When the node is executed it will go through all the steps we discussed of trying the different specialized classes and once it finds a success it will perform a rewrite and replace itself with a new subclass of SymbolNode. For example, if the symbol was storing a long then after calling readLong and getting back a response it would replace SymbolUninitializedNode with SymbolLongNode and all further calls to the node will go directly to readLong; and we didn’t have to write any of it!

Wow. Executing symbols has a lot more in it than I originally thought, but it’s all handled for us under the covers. The code you write is still simple and focused on custom methods for your types. Now let’s move onto another important but tricky part of Truffle: function calls.

Function Invocation

Function calls are a big part of Truffle probably because they are ripe with potential optimizations. You can potentially combine multiple function calls into one, change virtual calls to direct calls or maybe eliminate it if it’s not necessary. Therefore Truffle needs to be at the center of your function creation and function calling.

Mumbler has very simple call semantics. The complicated part of looking up the function is done in SymbolNode. When invoking we’ll just assume we have a function and throw an exception if something unexpected happens. The steps are similar to what we did in our simple interpreter. We’ll evaluate our arguments then apply them to our function. We’ll return the result of the last node executed. In Truffle all functions start with a RootCallTarget so we’ll call call with our array of arguments. We also need to keep in mind that the first element in all function calls is the lexical scope. That means all arguments passed to the function are offset by one, or—to put it another way—they are 1-based. Let’s implement our InvokeNode.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 |

public class InvokeNode extends MumblerNode { @Child protected MumblerNode functionNode; @Children protected final MumblerNode[] argumentNodes; @Child protected IndirectCallNode callNode; public InvokeNode(MumblerNode functionNode, MumblerNode[] argumentNodes) { this.functionNode = functionNode; this.argumentNodes = argumentNodes; this.callNode = Truffle.getRuntime().createIndirectCallNode(); } @Override @ExplodeLoop public Object execute(VirtualFrame virtualFrame) { MumblerFunction function = this.evaluateFunction(virtualFrame); CompilerAsserts.compilationConstant(this.argumentNodes.length); Object[] argumentValues = new Object[this.argumentNodes.length + 1]; argumentValues[0] = function.getLexicalScope(); for (int i=0; i<this.argumentNodes.length; i++) { argumentValues[i+1] = this.argumentNodes[i].execute(virtualFrame); } return this.callNode.call(virtualFrame, function.callTarget, argumentValues); } private MumblerFunction evaluateFunction(VirtualFrame virtualFrame) { try { return this.functionNode.executeMumblerFunction(virtualFrame); } catch (UnexpectedResultException e) { throw new UnsupportedSpecializationException(this, new Node[] {this.functionNode}, e); } } @Override public String toString() { return "(apply " + this.functionNode + " " + Arrays.toString(this.argumentNodes) + ")"; } } |

At this point most of the code should look familiar. Our InvokeNode extends MumblerNode so we override execute. We have a constructor that has all the necessary objects passed to it and will be used in Reader. We call executeMumblerFunction on our function node since it must absolutely return a function type. If that call fails we throw an exception and give up. We then evaluate all the argument nodes and put them into an array. Again, remember the first element in the array is the lexical scope object so the length of the array is the length of the argument nodes plus one. We then make the actual function call.

There a couple of elements in the class that probably look unfamiliar. First, we mark our fieds with the @Child and @Children annotations. This tells truffle that these fields are special. They are sub-nodes of our AST. This additional information will help with automatic tree rewriting at runtime. It doesn’t really affect the code we write but should help with runtime performance. I also annotate execute with @ExplodeLoop loop for the same reason. This annotation tells Truffle that when it compiles this method it can unroll the for loop since the number of iterations in the loop will not change. The call to CompilerAsserts.compilationConstant further confirms that. The code is simple and only contains a few extra lines to help Truffle gather more information about our language characteristics.

I kept the code simple because Mumbler’s function lookup is simple. In other languages with more complicated method lookup like Java (is this method an instance method, static method, the parent’s instance method…?) the function/method that is ultimately called could be much more complicated. We have to worry about any of that in Mumbler, but it’s something to keep in mind if you write languages that have classes (e.g., Ruby) or inheritance (e.g., Javascript).

We create an IndirectCallNode and then call it with our scope (VirtualFrame), the function (the call target since that’s the important part) and our arguments. There is a DirectCallNode we could use. Truffle could make more optimizations since a DirectCallNode assumes the function reference will not change. That would require more bookkeeping and rolling back or updating if that assumption becomes invalid. For the moment I’ll stick with IndirectCallNode and come back to later if we need to speed up Mumbler in the future.

Implement Mumbler’s Special Forms

We can now read variables and call functions. Let’s round that out by implementing our special forms to define variables and create functions. We’ll also implement if and quote while we’re at it. We’ll start with the simple if node.

IfNode

There shouldn’t be anything that surprises you in our implementation of if. You’ve seen all the pieces. Our IfNode will have 3 sub-nodes: the test node, the then node and the else node. We’ll execute the test node and if it returns false or an empty list, we’ll execute the else node or else we execute the then node. Let’s do this.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 |

public class IfNode extends MumblerNode { @Child private MumblerNode testNode; @Child private MumblerNode thenNode; @Child private MumblerNode elseNode; private final ConditionProfile conditionProfile = ConditionProfile.createBinaryProfile(); public IfNode(MumblerNode testNode, MumblerNode thenNode, MumblerNode elseNode) { this.testNode = testNode; this.thenNode = thenNode; this.elseNode = elseNode; } @Override public Object execute(VirtualFrame virtualFrame) { if (this.conditionProfile.profile(this.testResult(virtualFrame))) { return this.thenNode.execute(virtualFrame); } else { return this.elseNode.execute(virtualFrame); } } private boolean testResult(VirtualFrame virtualFrame) { try { return this.testNode.executeBoolean(virtualFrame); } catch (UnexpectedResultException e) { Object result = this.testNode.execute(virtualFrame); return result != MumblerList.EMPTY; } } } |

Okay, I lied. There should be at least one thing that you don’t recognize here. The ConditionProfile class is there to speculate on which branch is going to be taken. Usually an if clause goes the same way so we want that branch to be much more optimized than the branch less often taken. ConditionProfile does that work for us.

The other part that may confuse you is the testResult method. In Mumbler the only things that can trigger the else expression to execute are the #f value and the empty list. We’re assuming that #f is going to be used more often so we optimistically run executeBoolean. If that assumption turns out to be wrong an UnexpectedResultException is thrown then we try the generic execute and check to see if it’s the empty list.

QuoteNode

The QuoteNode should be even simpler. We basically just return value we were passed at creation. The only tricky part is that we want to avoid boxing as usual so we need special fields for long and boolean and make sure execute calls them directly. You know what that means: node rewriting. We’ll use the same trick we used in SymbolNode. We just need a NodeField to keep track of the type plus the actual value.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 |

@NodeChild("literalNode") @NodeField(name = "kind", type = QuoteKind.class) public abstract class QuoteNode extends MumblerNode { public static enum QuoteKind { LONG, BOOLEAN, SYMBOL, LIST } protected abstract QuoteKind getKind(); @Specialization(guards = "isLongKind") protected long quoteLong(VirtualFrame virtualFrame, long value) { return value; } @Specialization(guards = "isBooleanKind") protected boolean quoteBoolean(VirtualFrame virtualFrame, boolean value) { return value; } @Specialization(contains = {"quoteLong", "quoteBoolean"}) protected Object quote(VirtualFrame virtualFrame, Object value) { return value; } protected boolean isLongKind() { return this.getKind() == QuoteKind.LONG; } protected boolean isBooleanKind() { return this.getKind() == QuoteKind.BOOLEAN; } } |

The code may look a little different than SymbolNode but it utilizes the same Truffle DSL. We state our QuoteNode has one sub-node called “literalNode” that will contain the actual value. We also have a field that determines the type of the value so we can call the right specialized method. We use the @Specialization annotation again, but this time we use the guards value to perform the correct check. We want to check the value stored in kind and not the type of the value and guards allow us to do that.

Now Truffle will use quoteLong (if isLongKind returns true) or else move to quoteBoolean and so on. The node will be rewritten just like in SymbolNode so all further calls will be fast.

DefineNode

DefineNode should be a simple set of operations into Truffle’s frame object, right? Without further ado let’s check it out.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 |

@NodeChild("valueNode") @NodeField(name = "slot", type = FrameSlot.class) public abstract class DefineNode extends MumblerNode { protected abstract FrameSlot getSlot(); @Specialization(guards = "isLongKind") protected long writeLong(VirtualFrame virtualFrame, long value) { virtualFrame.setLong(this.getSlot(), value); return value; } @Specialization(guards = "isBooleanKind") protected boolean writeBoolean(VirtualFrame virtualFrame, boolean value) { virtualFrame.setBoolean(this.getSlot(), value); return value; } @Specialization(contains = {"writeLong", "writeBoolean"}) protected Object write(VirtualFrame virtualFrame, Object value) { FrameSlot slot = this.getSlot(); if (slot.getKind() != FrameSlotKind.Object) { CompilerDirectives.transferToInterpreterAndInvalidate(); slot.setKind(FrameSlotKind.Object); } virtualFrame.setObject(slot, value); return value; } protected boolean isLongKind() { return this.getSlot().getKind() == FrameSlotKind.Long; } protected boolean isBooleanKind() { return this.getSlot().getKind() == FrameSlotKind.Boolean; } } |

It looks much like QuoteNode. It uses Truffle the same way except instead of the guards checking a custom enum it checks FrameSlotKind for the correct type. The other big difference is inside the generic write method. If the define call falls back to the generic write method (that is, we’re not storing a long or boolean) we want to make sure the kind is consistent so we set it to Object and throw away any optimizations made for the primitive types. Outside of this type juggling all we’re doing is calling the proper set method on our virtual frame.

LambdaNode

On the surface, a LambdaNode is pretty simple. We want to return a MumblerFunction object. What’s in a MumblerFunction object? A MumblerFunction just contains a RootCallTarget. That’s where the interesting part exists. We need to create an instance of RootCallTarget to pass to MumblerFunction.

You create a RootCallTarget object by calling TruffleRuntime.createCallTarget with a subclass of com.oracle.truffle.api.nodes.RootNode. That means most of the interesting logic we had in the lambda special form in our simple interpreter will go into our RootNode subclass. What interesting logic is that? We create a new lexical scope, we bind argument values to formal parameter names and we return the result of the last expression.

Before we delve into our RootNode subclass let’s write our LambdaNode that returns a MumblerFunction object.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 |

@NodeField(name = "function", type = MumblerFunction.class) public abstract class LambdaNode extends MumblerNode { public abstract MumblerFunction getFunction(); private boolean scopeSet = false; @Specialization(guards = "isScopeSet") public MumblerFunction getScopedFunction(VirtualFrame virtualFrame) { return this.getFunction(); } @Specialization(contains = {"getScopedFunction"}) public Object getMumblerFunction(VirtualFrame virtualFrame) { MumblerFunction function = this.getFunction(); function.setLexicalScope(virtualFrame.materialize()); return function; } protected boolean isScopeSet() { return this.scopeSet; } public static MumblerFunction createMumblerFunction(RootNode rootNode, VirtualFrame currentFrame) { return new MumblerFunction( Truffle.getRuntime().createCallTarget(rootNode)); } } |

We return our MumblerFunction object when the node is executed but set the lexical scope beforehand. We only have the lexical scope available at runtime or else we would set it when we create MumblerFunction. We then do some node rewriting again to skip setting the lexical scope over and over. It doesn’t save much, but it’s also simple to implement because of Truffle’s DSL.

Simple enough, but how do we create this MumblerFunction object? We call its constructor and pass in a RootCallTarget we created from TruffleRuntime.createCallTarget. Let’s create our RootNode subclass.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 |

public class MumblerRootNode extends RootNode { @Children private final MumblerNode[] bodyNodes; public MumblerRootNode(MumblerNode[] bodyNodes, FrameDescriptor frameDescriptor) { super(null, frameDescriptor); this.bodyNodes = bodyNodes; } @Override @ExplodeLoop public Object execute(VirtualFrame virtualFrame) { int secondToLast = this.bodyNodes.length - 1; CompilerAsserts.compilationConstant(secondToLast); for (int i=0; i<secondToLast; i++) { this.bodyNodes[i].execute(virtualFrame); } return this.bodyNodes[secondToLast].execute(virtualFrame); } } |

Well, it does one of the tasks; it executes the lambda body and returns the last node’s result. That’s okay though. We just need to bind the arguments to the current frame. Our current MumblerRootNode class gives us the power to do that. We can bind the args as additional nodes we prepend to the body of the function. That would be more modular and more easily extendable in the future. In fact, we don’t even need a new argument binding class. We can just reuse our DefineNode. All we need is a node to read the value from the arguments array in VirtualFrame. We still have that one twist. The first element in the array is our lexical scope object. We have to offset everything by 1.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 |

public class ReadArgumentNode extends MumblerNode { public final int argumentIndex; public ReadArgumentNode(int argumentIndex) { this.argumentIndex = argumentIndex; } @Override public Object execute(VirtualFrame virtualFrame) { if (!this.isArgumentIndexInRange(virtualFrame, this.argumentIndex)) { throw new IllegalArgumentException("Not enough arguments passed"); } return this.getArgument(virtualFrame, this.argumentIndex); } } |

The methods isArgumentIndexInRange and getArgument do what you’d expect except they offset the index by one to account for the ever-present lexical object. That’s all there is to it.

We now have all the pieces we need to create an instance of MumblerRootNode that binds the function arguments, executes the body expressions and returns the last expression. We’ll create a static method to tie all this together.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 |

public static MumblerRootNode create(FrameSlot[] argumentNames, MumblerNode[] bodyNodes, FrameDescriptor frameDescriptor) { MumblerNode[] allNodes = new MumblerNode[argumentNames.length + bodyNodes.length]; for (int i=0; i<argumentNames.length; i++) { allNodes[i] = DefineNodeFactory.create( new ReadArgumentNode(i), argumentNames[i]); } System.arraycopy(bodyNodes, 0, allNodes, argumentNames.length, bodyNodes.length); return new MumblerRootNode(allNodes, frameDescriptor); } |

We basically just combine everything into one array and transform our list of argument names (passed as FrameSlot objects) into DefineNode objects where the value is returned by the ReadArgumentNode. We just copy the body nodes over as-is.

We also create a static function in MumblerFunction to create a MumblerFunction instance from argument names and a body of nodes.

1 2 3 4 5 6 |

public static MumblerFunction create(FrameSlot[] arguments, MumblerNode[] bodyNodes, FrameDescriptor frameDescriptor) { return new MumblerFunction( Truffle.getRuntime().createCallTarget( MumblerRootNode.create(arguments, bodyNodes, frameDescriptor))); } |

We’ll again punt on calling these functions until we update Reader, but there should be nothing tricky there. We just need to create FrameSlot objects with Truffle’s APIs.

With that we’re done with all our special forms. We have a complete langauge! Kinda. We need to bootstrap our environment with some builtin functions like our simple interpreter. Let’s add some basic arithmetic and list functions.

Add Builtin Methods

We’re in the homestretch. All the big Truffle concepts have been covered. We’re just completing our language with some basic functions. I’ll show a couple of builtin functions and let you refer to the repo if you want to see all implementations of the functions.

We’ll start with a simple one. Let’s print a value to standard out.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 |

@NodeInfo(shortName = "println") public abstract class PrintlnBuiltinNode extends BuiltinNode { @Specialization public long println(long value) { System.out.println(value); return value; } @Specialization public boolean println(boolean value) { System.out.println(value); return value; } @Specialization public Object println(Object value) { System.out.println(value); return value; } } |

Just a typical usage of Truffle’s DSL. We return the value because our language only has expressions so everything must return something and the value printed sounds like a reasonable choice. We extend a new class BuiltinNode. Let’s look at what’s in there.

1 2 3 |

@NodeChild(value = "arguments", type = MumblerNode[].class) public abstract class BuiltinNode extends MumblerNode { } |

It’s even easier. It has nothing. It just declared a sub-node named arguments. This will stored all the arguments passed to this node and any sub-classed nodes. We don’t use the arguments directly (which is why we don’t declare an abstract getter method) but the generated classes conveniently convert an array of nodes to the arguments we get in our methods (like println).

Let’s look at one more function. Here’s how I wrote the addition node.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 |

@NodeInfo(shortName = "+") public abstract class AddBuiltinNode extends BuiltinNode { @Specialization public long add(long value0, long value1) { return value0 + value1; } } |

Even simpler since add is only defined for numbers (long). You may notice something though. The add method only takes 2 arguments. + in our simple interpreter took a variable number of arguments. We’re cutting some corners here because + in our Truffle version takes exactly two arguments. I’m doing this for expediency. We have all the tools we need to create a variable argument function implementation with node rewriting, but that would take more time and effort and not teach us anything new about Truffle. Plus, our examples only require two arguments so we’ll just proceed ahead and maybe come back and implement varargs if we need to. Right now, it’s a case of YAGNI.

We’ll continue on in this process creating all our arithmetic nodes (-, *, /, %) and our list operation nodes (list, car, cdr). You can see those implementations on GitHub.

We’re still missing one crucial piece that ties our nodes to functions. We’ve only created AST nodes that perform these various actions. We don’t have actual functions. Just like we did with lambda, we need to put our node into a RootNode instance. We can skip argument bindings, but we still need to read/execute the argument nodes and pass them to our arguments node child we defined in BuiltinNode. Let’s write a create method that ties all the pieces together.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 |

public static MumblerFunction createBuiltinFunction( NodeFactory<? extends BuiltinNode> factory, FrameDescriptor frameDescriptor) { int argumentCount = factory.getExecutionSignature().size(); MumblerNode[] argumentNodes = new MumblerNode[argumentCount]; for (int i=0; i<argumentCount; i++) { argumentNodes[i] = new ReadArgumentNode(i); } BuiltinNode node = factory.createNode((Object) argumentNodes); return new MumblerFunction(Truffle.getRuntime().createCallTarget( new MumblerRootNode(new MumblerNode[] {node}, frameDescriptor))); } |

Our method takes any factory class that creates subclasses of BuiltinNode. We loop over the expected number of arguments (as defined by our BuiltinNode subclasses), execute the argument nodes and put them into an array. We then create an instance of our node with that list of argument values. We put that in a MumblerRootNode and then put that in a MumblerFunction and we’re done. Now we can have a MumblerFunction object for every one of our builtin nodes.

We can now create our top level namespace with our newly created builtin functions.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 |

private static VirtualFrame createTopFrame(FrameDescriptor frameDescriptor) { VirtualFrame virtualFrame = Truffle.getRuntime().createVirtualFrame( new Object[] {}, frameDescriptor); virtualFrame.setObject(frameDescriptor.addFrameSlot("println"), createBuiltinFunction(PrintlnBuiltinNodeFactory.getInstance())); virtualFrame.setObject(frameDescriptor.addFrameSlot("+"), createBuiltinFunction(AddBuiltinNodeFactory.getInstance())); // more buitins ... virtualFrame.setObject(frameDescriptor.addFrameSlot("now"), createBuiltinFunction(NowBuiltinNodeFactory.getInstance())); return virtualFrame; } |

We see how we get a FrameSlot here. We create from a FrameDescriptor object (which comes from our current frame). The FrameDescriptor keeps track of where values are stored in frames. Truffle has multiple tricks to make variable access fast and frame descriptors is where all that information goes.

We’re done with our syntax tree! With a tree of nodes we can just call execute and it’ll all work. Of course, we still need to create our tree. Time to convert our old Reader class to create our Truffle nodes.

Update Reader to Return New Truffle Nodes

Our Reader needs to make a big change. Instead of returning our Mumbler data types it now has to return Truffle nodes. We also need to add one important feature. We need a new FrameDescriptor object whenever we enter a new scope. That means when we see a lambda we need to create a new FrameDescriptor object and get all our FrameSlot objects from that. The tracking of the current FrameDescriptor won’t be very hard. We’ll just create a Stack data structure and push/pop frame descriptors as we enter/exit lambda bodies. The bigger issue is this will complicate reading lists since we have to do something special for lambdas.

So how do we make these changes? Well, let’s not forget we have a working Reader from our simple interpreter. Why not just re-purpose our existing reader and convert every datatype to its matching Truffle node. Our literal long and boolean nodes will be simple conversions, and symbols shouldn’t be too hard (as long as we have our frame descriptor stack working).

So how do we update our Reader class and make minimal modifcations to working code? I’ll add a conversion process after the reader step. The Reader returns our Mumbler data structures but we wrap them in a class that’ll do the conversion. The wrapper classes will implement a simple interface.

1 2 3 |

interface Convertible { public MumblerNode convert(); } |

We visit every element in the tree and create a parallel structure of Truffle nodes. We’ll just update our code to return a new class for simple conversion to Truffle nodes.

Here’s our wrapped classes for long and boolean.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 |

private static class LiteralConvertible implements Convertible { final MumblerNode value; public LiteralConvertible(MumblerNode value) { this.value = value; } @Override public MumblerNode convert() { return this.value; } } |

It’s very simple since we don’t have to do anything with our literal elements. We just create our literal nodes and simply wrap it with our LiteralConvertible class. Here’s how we’ll use LiteralConvertible.

1 2 3 4 5 |

// for numbers return new LiteralConvertible(new NumberNode(/* get number value */)); // for booleans return new LiteralConvertible(booleanValue ? BooleanNode.TRUE : BooleanNode.FALSE); |

So our conversion is just a simple return. The conversion of symbols is a little more complicated (but not much).

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 |

private static class SymbolConvertible implements Convertible { final String name; public SymbolConvertible(String name) { this.name = name; } @Override public MumblerNode convert() { return SymbolNodeFactory.create( frameDescriptors.peek().findOrAddFrameSlot(this.name)); } } |

We take the token of the symbol and create a FrameSlot instance.

The real work is done when we convert Mumbler list. That’s because we have to deal with special forms when converting lists. As I mentioned earlier, we need to keep track of which scope we’re in because we have separate FrameDescriptor objects for every scope, and every scope is defined by lambda. We still have our other special forms but they shouldn’t be too bad. The other twist is since we can have lists within lists our algorithms have to be recursive. So let’s look how we’re going to convert lists.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 |

private static class ListConvertible implements Convertible { final List<Convertible> list; public ListConvertible(List<Convertible> list) { this.list = list; } @Override public MumblerNode convert() { if (this.list.size() == 0) { return new LiteralListNode(MumblerList.EMPTY); } else if (this.list.get(0) instanceof SymbolConvertible && this.isSpecialForm((SymbolConvertible) this.list.get(0))) { return this.toSpecialForm(); } return new InvokeNode(this.list.get(0) .convert(frameDescriptor), this.list.subList(1, this.list.size()) .stream() .map(conv -> conv.convert(frameDescriptor)) .toArray(size -> new MumblerNode[size])); } // more... } |

First off we branch into three possible results: an empty list, a special form or a normal function call. We return a literal node for the empty list when we encounter… an empty list. Makes sense. We kick off to another method to create special forms so as not to clutter this method. Lastly create a normal function call node. The InvokeNode creation is pretty simple. We pass in the first element as the function node and the rest of the elements in the list are the arguments.

So the final piece is converting lists to special forms. Let’s show toSpecialForm.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 |

private MumblerNode toSpecialForm() { SymbolConvertible symbol = (SymbolConvertible) this.list.get(0); switch (symbol.name) { case "quote": return quote(this.list.get(1)); case "if": return new IfNode(this.list.get(1).convert(), this.list.get(2).convert(), this.list.get(3).convert()); case "define": return DefineNodeFactory.create(this.list.get(2).convert(), frameDescriptors.peek().findOrAddFrameSlot( ((SymbolConvertible) this.list.get(1)).name)); case "lambda": frameDescriptors.push(new FrameDescriptor()); List<FrameSlot> formalParameters = new ArrayList<>(); for (Convertible arg : ((ListConvertible) this.list.get(1)).list) { formalParameters.add(((SymbolNode) arg.convert()).getSlot()); } List<MumblerNode> bodyNodes = new ArrayList<>(); for (Convertible bodyConv : this.list.subList(2, this.list.size())) { bodyNodes.add(bodyConv.convert()); } frameDescriptors.pop(); MumblerFunction function = MumblerFunction.create( formalParameters.toArray(new FrameSlot[] {}), bodyNodes.toArray(new MumblerNode[] {})); return LambdaNodeFactory.create(function); default: throw new IllegalStateException("Unknown special form"); } } |

We have a string switch statement with four entries for the four special forms. We call a separate method to do quote. I won’t show the method, but it’s what you’d expect: we see what type the element is and return the literal node for that type. Next is if and it’s a simple placing of the 3 parts of the if expressions (test, then, else) and creating an IfNode. define is equally simple in that I just pull out the various elements and create a node. The one twist is that we get the current FrameDescriptor object and get a FrameSlot object, but we’ve seen that before now. Finally we create lambda.

The lambda portion is a little more beefy but it’s pretty simple. First we push a new FrameDescriptor object onto our stack of frame descriptors. We’ve now fulfilled half of the requirement we had when writing our new reader. The second hand you can see towards the end of the case block where we pop off the frame descriptor. Again, the new FrameDescriptor object is only used while we’re in the lambda body. After we’ve converted all the lambda body expressions we’re done with the lambda’s frame descriptor so we discard it. In between pushing and popping frame descriptors we do two other things. We go through the list of parameter names and create FrameSlot instances for each of them. Next we run through the body of the lambda (which is all elements of the list after the first two) and convert them to MumblerNode objects. As we convert elements the new frame descriptor will be used whenever a symbol is encoutered. If another lambda is created inside our lambda then we just push another frame descriptor and go on our merry way. The last thing we do is create a MumblerFunction object then stick that in a LambdaNode object and we’re done.

We had to add a few more classes to handle the conversion from Mumbler data types, but it was done quite easily. If Java allowed mixins on Long and Boolean maybe we could’ve done it a little more elegantly, but the end result is still easy to follow.

Updating Main Class

One more class to go. Time to update SimpleMumblerMain to get the Truffle VM rolling. First, let’s update the name to something more… Truffle-y; like TruffleMumblerMain.

The two main things we need to do here is set up our environment (i.e., populate our top level lexical scope with our builtin functions) and kick off the evaluation of our nodes. We already showed how we create a frame when we wrote our builtin functions and called the method createTopFrame. I’ll just show the last bit.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 |

// Inside TruffleMumblerMain private static void runMumbler(String filename) throws IOException { VirtualFrame topFrame = createTopFrame(Reader.frameDescriptors.peek()); MumblerList<MumblerNode> nodes = Reader.read(new FileInputStream(filename)); execute(nodes, topFrame); } private static Object execute(MumblerList<MumblerNode> nodes, VirtualFrame topFrame) { FrameDescriptor frameDescriptor = topFrame.getFrameDescriptor(); MumblerFunction function = MumblerFunction.create(new FrameSlot[] {}, StreamSupport.stream(nodes.spliterator(), false) .toArray(size -> new MumblerNode[size]), frameDescriptor); DirectCallNode directCallNode = Truffle.getRuntime() .createDirectCallNode(function.callTarget); return directCallNode.call( topFrame, new Object[] {topFrame.materialize()}); } |

Assuming we’re executing a file, we create our AST from the file in runMumbler then we call execute to do the dirty work. The trick here is to create a “main” function to kick off the execution. We create a MumblerFunction instance on the fly then create a DirectCallNode instance since we know this method will never change and then call call with our lexical scope as the first and only argument. I reuse the top level frame as the VirtualFrame object for the “main” function but that isn’t necessary.

The reason for creating a “main” function is so that all our nodes have a parent and Truffle can perform node rewriting even on the top level expressions. And this way they are functions all the way down, and there are no special work needed for the top level expressions. A code of a file is just the body of an argument-less function.

With that, we’re done with our Truffle implementation. Sure, there’s plenty more we can do (which I’ll cover later), but we have a working implementation. Let’s see how it performs, shall we.

Benchmarks

As reminder, here’s how our simple interpreter did last time:

mumbler (simple)

--------------

1346269

('computation-time: 1502)

total time: 1644So it took about a second and half to compute the 30th element of the fibonacci sequence with our inefficient algorithm.

Let’s take that fibonacci implementation and run it with our new Truffle interpreter. I used the -server flag when running the Graal VM (command: <path-to-graal-vm> -server -jar <my-vm-jar> <path-to-script>) The median speed over 5 runs.

mumbler (truffle)

--------------

1346269

('computation-time: 6348)

total time: 7874Ouch. That’s a helluva jump. Now, we didn’t utilize all of Truffle’s capabilities, but I wasn’t expecting such a huge jump. That’s almost a 5x slowdown.

Did I do something seriously wrong? Well, Truffle comes with an example language implementation called Simple Language. That’s supposed to be a good starting point that uses most of Truffle’s tricks to speed up your interpreter. Let’s try that language out and see what we get. Here’s the code for Simple Language:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 |

function fibonacci(n) { if (n < 2) { return 1; else { return fibonacci(n - 2) + fibonacci(n - 1); } } function main() { start = nanoTime(); println(fibonacci(30)); end = nanoTime(); println("computation time: " + (end - start) / 1000); } |

Using the same flags as before, here’s the median benchmark after 5 runs:

simple language

--------------

== running on Graal Truffle Runtime

1346269

computation time: 3112407

total time: 4568Okay, it’s faster than our implementation so we know there’s room for improvement, but it’s still about 3x slower than our simple implementation.

Perhaps there are some “make it fast” build or VM flags I’m not aware of, but so far things aren’t looking very good for Graal. Of course, this is still in active development so the team I’m sure have some more tricks up there sleeve. Perhaps our simple fibnonacci app is a little contrived, but I was hoping for something a little more snappy.

What’s (Maybe) Next

We can still improve Mumbler’s Truffle interpreter. I’m sure the way we look up variables is slow. We could cache the value in the current frame for faster, future lookup. Our function calls use IndirectCallNode instances. We could see some improvement by doing some node rewriting and using DirectCallNode objects.

Truffle also has some tools to visualize the interpreter. We haven’t explored using those tools yet. Those could come in handy in finding bottlenecks and help improve debugging.

Hopefully in the meantime Truffle gets faster without having to do anything.