Writing a Language in Truffle. Part 4: Adding Features the Truffle Way

I ended last time with a lisp that had the bare minimum of features and had a reached an acceptable speed. Now it’s time to make Mumbler a more useful languages with a couple of new features: arbitrary precision integers and—what no lisp should be without—tail call optimization.

I don’t want to undo all the work it took to make Mumbler fast, so I’m going to show how Truffle can help to include these features and still keep the langauge fast.

Table of Contents

- Arbitrary Precision Arithmetic

- A Lisp Birthright: Tail Call Optimization

- Conclusion

- Update: Some Benchmark Numbers

Arbitrary Precision Arithmetic

If you go way back to the first post I stated that I was going to limit Mumbler’s number types to long in the interest of simplifying the implementation of the interpreter. Well now I have the interpreter written and the users are (theoretically) clamouring for more robust arithmetic. Let’s take a look at how we would implement it.

The thing I don’t want to do is replace our use of long with BigInteger throughout our interpreter. That would wreck havoc on performance when most uses of numbers will stay within the size of a long. What I want is to only fallback on BigInteger if the user specifies a number that can’t fit in a long or an arithmetic operation results in a number that is too big.

Adding BigInteger to Mumbler’s Types

Since I’m adding a new data type to Mumbler’s interpreter I need to update the class that defines all the built-in types. So I crack open MumblerTypes and add BigInteger

@TypeSystem({long.class, boolean.class, BigInteger.class, MumblerFunction.class,

MumblerSymbol.class, MumblerList.class})

public class MumblerTypes {

@ImplicitCast

public static BigInteger castBigInteger(long value) {

return BigInteger.valueOf(value);

}

}The change is simple enough. I add BigInteger.class to the list in @TypeSystem. Remember that the order of the types matters. Types that appear earlier bind more tightly than later ones. If I put BigInteger before long than operations would try to return BigInteger first, succeed, and never get to long. Bad news for performance.

The other change is the new castBigInteger method. The method does a simple conversion from long to BigInteger. The key is the @ImplicitCast annotation. The annotation tells Truffle a long can be converted to a BigInteger, and use this method if we ever need to do that.

The last thing I need to do to make BigInteger a first class citizen is allow all MumblerNode objects to return a BigInteger object. So we just add another method to our base node.

@TypeSystemReference(MumblerTypes.class)

@NodeInfo(language = "Mumbler Language", description = "The abstract base node for all expressions")

public abstract class MumblerNode extends Node {

// other execute methods...

public BigInteger executeBigInteger(VirtualFrame virtualFrame)

throws UnexpectedResultException {

return MumblerTypesGen.expectBigInteger(this.execute(virtualFrame));

}

}That’s it. Now all nodes can return BigInteger numbers. One problem, nothing yet returns BigInteger numbers. Where would we want to return arbitrarily long numbers? Why, when we add, substract or multiply two numbers and they no longer fit in a long. Of course!

The Truffle Implementation

The first problem is Java’s +, - and * operators just wrap around if we go passed MAX/MIN_VALUE. Thankfully, Java8 added new methods to java.lang.Math that will throw an exception if the operation overflows. Since Truffle supports Java7 they backported these methods to their com.oracle.truffle.api.ExactMath class. Now we can fallback on BigInteger if the value won’t fit in a long. For example, the AddBuiltinNode’s add method now looks like this.

public long add(long value0, long value1) {

return ExactMath.addExact(value0, value1);

}We still need to catch the exception. Truffle’s @Specialization annotation has a rewriteOn field where we can say “if an ArithmeticException is thrown rewrite the AST and upcast long to BigInteger.” Of course, if we’re going to upcast to BigInteger we’ll need a method add two BigInteger objects.

@NodeInfo(shortName = "+")

@GenerateNodeFactory

public abstract class AddBuiltinNode extends BuiltinNode {

@Specialization(rewriteOn = ArithmeticException.class)

public long add(long value0, long value1) {

return ExactMath.addExact(value0, value1);

}

@Specialization

protected BigInteger add(BigInteger value0, BigInteger value1) {

return value0.add(value1);

}

}This is the new AddBuiltinNode class. It contains the old add method for long but now uses ExactMath.addExact, and the @Specialization annotation now states to rewrite the AST on an ArithmeticException. We’ve also added add for BigInteger. Since we don’t expect any exception here it just adds and returns.

That’s all we need to do to upgrade addition to gracefully move to BigInteger if long becomes too small. The changes to subtraction and multiplication work the same way.

Adding Literal BigInteger Numbers

The final piece of the arbitrary precision puzzle is allowing users to write any number and have Mumbler create the proper number type. The code to create literal long nodes is in place. I just need to add a literal node for BigInteger if the number can’t be cast to long. First the literal BigIntegerNode class.

public class BigIntegerNode extends MumblerNode {

public final BigInteger value;

public BigIntegerNode(BigInteger value) {

this.value = value;

}

@Override

public BigInteger executeBigInteger(VirtualFrame virtualFrame) {

return this.value;

}

@Override

public Object execute(VirtualFrame virtualFrame) {

return this.value;

}

}Very simple. Just return the BigInteger object. So where do I create these objects? I have to modify the Reader to create BigIntegerNode objects if LongNode won’t work. I’ll optimistically try to create a long and only if there’s an exception will Reader fallback on BigIntegerNode. Here’s the relevent part of the Reader.readNumber.

private static Convertible readNumber(PushbackReader pstream)

throws IOException {

// read number from PushbackReader...

try {

return new LiteralConvertible(new LongNode(

Long.valueOf(buffer.toString(), 10)));

} catch (NumberFormatException e) {

// Number doesn't fit in a long. Using BigInteger.

return new LiteralConvertible(new BigIntegerNode(

new BigInteger(buffer.toString(), 10)));

}

}If Long.valueOf throws a NumberFormatException (which in this method will only happen if the number is too big to fit into a long value) then we create a BigIntegerNode. We’re done. We don’t need to make any other changes. Now you can add to your heart’s content!

A Lisp Birthright: Tail Call Optimization

Perhaps “birthright” is a little strong. There are lisps out there without tail call optimization (TCO) like Clojure though it’s not for lack of trying. The JVM doesn’t natively support tail call optimization, but now with Truffle we have a way a way around So many languages have on the JVM would love to have TCO and now we have salvation from imperative purgatory. Hooray!

For a language without explicit loop constructs like for or while, Mumbler needs to be extra careful not to blow the call stack. This kinda makes TCO a requirement. A quick test on my machine shows Mumbler fills up the call stack after about 800 iterations. So don’t expect do anything more than 800 times or your program will crash. Not very pleasant.

To build this feature I had to bone up on TCO. As a user of Scheme, I was famililar at how to use TCO, but not how would I go about implementing it. In fact, I wasn’t sure what constituted TCO. I mostly relied on TCO when I wrote recursive functions, but after reading the Wikipedia page on Tail Calls I realized that you could do TCO on any function call that’s the last (leaf) node of the AST. So let’s go and optimize all function calls in the tail position.

What is Tail Call Optimization

But first, what does it mean to optimize a tail calls? Like I said, the goal is to make sure we don’t get a StackOverflowException—especially if we have a recursive function that will have a lot of iterations. So how do we avoid this? The basic idea behind tail call optimization is:

Once you have nothing left to do in your current function (aside from the final function call) you don't need that function's scope anymore. You can jump back to the caller with the arguments and the lexical scope and call the final function from the caller.

This way, a recursive function will take only two entry in the call stack: the caller’s frame and the current function being executed. Of course if function mades other function calls within that aren’t in the tail position those will add to the call stack. That’s why you sometimes have to rearrange a function body so it is optimized for tail calls.

Every time the last function is about to be called, you first jump back to the caller and call it from there. For example, say we were computing the factorial of a number, a prototypical lisp function. The code would look something like this:

(define factorial (lambda (n product)

(if (< n 2)

product

(factorial (- n 1) (* n product)))))Without TCO Mumbler would create a new frame on the call stack for every call to factorial like:

<main> <main> <main>

(fibonacci 3 1) (fibonacci 3 1) (fibonacci 3 1)

(fibonacci 2 3) (fibonacci 2 3)

(fibonacci 1 6)

You can see how quickly this grows even though we don’t need the intermediate frames. It would be great if we could have a stack more like:

<main> <main> <main> (fibonacci 3 1) (fibonacci 2 3) (fibonacci 1 6)

The one constant in all this is the top frame. The top frame can make all the intermediate calls on behalf of the functions and receive the result when we reach the terminal state (when n is less than 1). So how do we do that in Truffle?

Tail Call Optimization in Truffle

So how do we kick out of a function call? Well, we could call return with some special object that says “This is a tail call. Complete function call”, but that would get tedious having to check for a special object on every call and it won’t be efficient. Truffle doesn’t make us do that thankfully. Truffle uses Java’s other strategy for unwinding the call stack: exceptions.

Truffle has a special exception class ControlFlowException that should be used for all flow control. Graal has special knowledge of this class and its children so it can optimize away all the internal function calls. This way, control structures like for and while or even structures like break and return can be as fast in Graal as they are in regular Java.

So let’s create our special tail call exception.

public class TailCallException extends ControlFlowException {

public final CallTarget callTarget;

public final Object[] arguments;

public TailCallException(CallTarget callTarget, Object[] arguments) {

this.callTarget = callTarget;

this.arguments = arguments;

}

}That was easy. The class contains the function (CallTarget) that’s going to be called plus all the arguments. All the arguments have been evaluated before we throw the exception. The CallTarget objects are created when we build our functions. You can read the previous post on function creation to see how it’s created. With these two pieces of information I can make a function call. Technically, we need a VirtualFrame object but we’ll get that from the caller.

Starting a Tail Call

So when we’re about to execute that final node in the function’s AST, we want to throw a TailCallException instead. All function calls occur in the InvokeNode.execute method so let’s update that code.

@Override

@ExplodeLoop

public Object execute(VirtualFrame virtualFrame) {

MumblerFunction function = this.evaluateFunction(virtualFrame);

CompilerAsserts.compilationConstant(this.argumentNodes.length);

Object[] argumentValues = new Object[this.argumentNodes.length + 1];

argumentValues[0] = function.getLexicalScope();

for (int i=0; i<this.argumentNodes.length; i++) {

argumentValues[i+1] = this.argumentNodes[i].execute(virtualFrame);

}

if (CompilerAsserts.compilationConstant(this.isTail())) {

throw new TailCallException(function.callTarget, argumentValues);

} else {

return this.call(virtualFrame, function.callTarget, argumentValues);

}

}The method starts like before: evaluate the function, evaluate the arguments. After that we check if the node is in the tail position. I’ll show how that’s set later; for now assume it’s set to the correct value. There’s a call to CompilerAsserts.compilationConstant to tell Truffle this value is constant. A function call in the tail position isn’t going to move so we may as well eke out as much performance as we can. If the node is in the tail position then we create a TailCallException and throw it. If not we make the call like normal.

Catching a Tail Call

Starting a tail call was straightforward, but how do we catch a TailCallException? Furthermore, where do we catch a TailCallException?

I want to catch the exception in the body of the caller. So, when I call a function there’s a chance that function may say, “Hey, take care of this function call for me.” Okay, so when we call a function we have to wrap it in a try/catch in case it throws a TailCallException. But wait, what about the function call from TailCallException? Couldn’t that also throw another TailCallException? Yes! In the factorial example above the caller function () had to handle 3 tail calls. So not only do we have to handle the normal function, but we have to be prepared to catch any number of TailCallException. How will I do that? Let’s look at the InvokeNode.call method.

public Object call(VirtualFrame virtualFrame, CallTarget callTarget,

Object[] arguments) {

while (true) {

try {

return this.dispatchNode.executeDispatch(virtualFrame,

callTarget, arguments);

} catch (TailCallException e) {

callTarget = e.callTarget;

arguments = e.arguments;

}

}You can see buried underneath all the wrappings is a call to our dispatch node that will take care of the actual call. Outside of that we catch the TailCallException and keep trying until we return normally. We basically keep going around and call the dispatch node however many times it takes until a TailCallException is not thrown. If a call throws a TailCallException we catch it and start over with the new values.

Dispatching to the Right Function

If you recall when we implemented function calls, Truffle requires all CallTarget objects to be wrapped in a CallNode. Previously Mumbler was using the subclass DirectCallNode because it is faster, but it does have the limitation of only working for one function in one invocation node. That wasn’t really a limitation because one InvokeNode would only ever be linked to one function, but now that an InvokeNode has to handle tail calls the node may have to deal with other CallTarget objects. We can’t rely on one DirectCallNode anymore. We also don’t want to only use IndirectCallNode because it’s much slower. What do we do?

We implement a cache. We take the most common CallTarget objects and wrap them in DirectCallNode objects. To prevent an explosion of DirectCallNode creation I set a limit on the cache size. Once the limit is reached, we’ll fall back on IndirectCallNode for further function calls. This way we get the fast speeds of DirectCallNode for most functions, but everything still works in case the cache is full. All this logic is encapsulated in the DispatchNode children.

The dispatch node starts with UninitializedDispatchNode. The job of this node is to keep track of how big the dispatch cache is. If it exceeds the limit we fall back on IndirectCallNode. If not, we create a DirectCallNode for the current function and use it.

final public class UninitializedDispatchNode extends DispatchNode {

@Override

protected Object executeDispatch(VirtualFrame virtualFrame,

CallTarget callTarget, Object[] arguments) {

CompilerDirectives.transferToInterpreterAndInvalidate();

Node cur = this;

int depth = 0;

while (cur.getParent() instanceof DispatchNode) {

cur = cur.getParent();

depth++;

}

InvokeNode invokeNode = (InvokeNode) cur.getParent();

DispatchNode replacement;

if (depth < INLINE_CACHE_SIZE) {

// There's still room in the cache. Add a new DirectDispatchNode.

DispatchNode next = new UninitializedDispatchNode();

replacement = new DirectDispatchNode(next, callTarget);

this.replace(replacement);

} else {

replacement = new GenericDispatchNode();

invokeNode.dispatchNode.replace(replacement);

}

// Call function with newly created dispatch node.

return replacement.executeDispatch(virtualFrame, callTarget, arguments);

}

}Starting from the top, the first thing we do is call CompilerDirectives.transferToInterpreterAndInvalidate. This node doesn’t do anything except create other nodes and alters the AST. Graal will need to re-optimize the tree and transferToInterpreterAndInvalidate is how we tell Graal to do that. I then find the end of the linked list of dispatch nodes and also compute its size. I then check if the the max cache size is reached. If so, I switch to using GenericDispatchNode. If not, I create a new DirectDispatchNode. I stick a new UninitializedDispatchNode at the end so it can handle any future changes needed.

If the tail call has been caught there will be a cached DirectDispatchNode waiting for me to reuse. Graal can then inline it. Let’s see what DirectDispatchNode does.

public class DirectDispatchNode extends DispatchNode {

private final CallTarget cachedCallTarget;

@Child private DirectCallNode callCachedTargetNode;

@Child private DispatchNode nextNode;

public DirectDispatchNode(DispatchNode next, CallTarget callTarget) {

this.cachedCallTarget = callTarget;

this.callCachedTargetNode = Truffle.getRuntime().createDirectCallNode(

this.cachedCallTarget);

this.nextNode = next;

}

@Override

protected Object executeDispatch(VirtualFrame frame, CallTarget callTarget,

Object[] arguments) {

if (this.cachedCallTarget == callTarget) {

return this.callCachedTargetNode.call(frame, arguments);

}

return this.nextNode.executeDispatch(frame, callTarget, arguments);

}

}Pretty standard stuff for Truffle. We keep a reference to the CallTarget used to create the node, the DirectCallNode which I use to make the actual function call, and a reference to the next DispatchNode in the chain in case this isn’t the CallTarget we were looking for. The executeDispatch method couldn’t be simpler. We check if the CallTarget of the function is the same as the one used to create this node. If so, we call it. If not, we move one.

What if we get to the end of our cache and need to handle any CallTarget sent to us?

public class GenericDispatchNode extends DispatchNode {

@Child private IndirectCallNode callNode = Truffle.getRuntime()

.createIndirectCallNode();

@Override

protected Object executeDispatch(VirtualFrame virtualFrame,

CallTarget callTarget, Object[] argumentValues) {

return this.callNode.call(virtualFrame, callTarget, argumentValues);

}

}When you thought things couldn’t get simpler. We can reuse the same IndirectCallNode for all calls so we just pass in all the values to the IndirectCallNode.

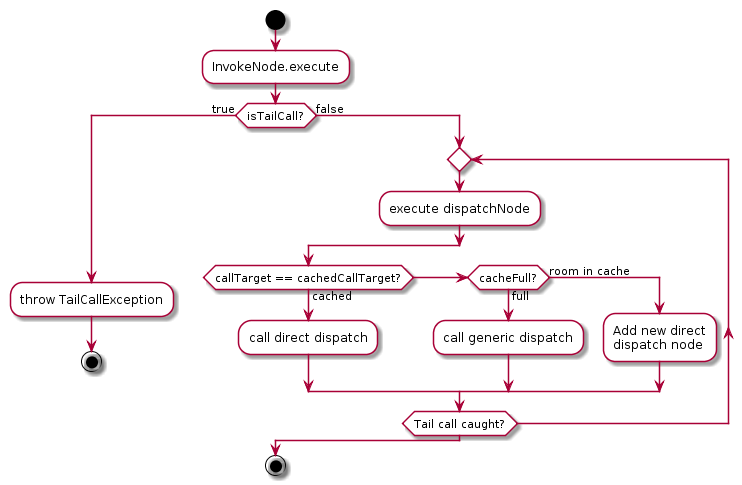

In case the description above was confusing, here’s a flow chart of how one InvokeNode handles tail calls.

Flow diagram for a function call

Setting Nodes as Tail

I have all the plumbing in place, but I still haven’t said how to set nodes as tails. On first glance it’s pretty simple: take the last node in a lambda body and set it as tail. There’s only one little wrinkle with that strategy: control flow nodes. Namely, if isn’t the tail, it’s the then/else nodes that are. In other lisps like Scheme the list of control structures can be quite long, but Mumbler only has to worry about if.

So first we add the method isTail to MumblerNode.

public abstract class MumblerNode extends Node {

@CompilationFinal

private boolean isTail = false;

public boolean isTail() {

return this.isTail;

}

public void setIsTail() {

this.isTail = true;

}

// rest of class...

}Since any node can be in the tail position of a function we need the predicate for all nodes. We’ll set the default to false since most nodes won’t be the last. We need to update the IfNode to propogate its “tailness” to its then/else nodes.

public class IfNode extends MumblerNode {

@Override

public void setIsTail() {

super.setIsTail();

this.thenNode.setIsTail();

this.elseNode.setIsTail();

}

// rest of class...

}That was simple. Now all that’s left is to set the last node in a lambda as a tail node. We modify Reader. While we create our LambdaNode we have to call setIsTail before we return the object.

// creating LambdaNode...

List<MumblerNode> bodyNodes = new ArrayList<>();

for (Convertible bodyConv : this.list.subList(2, this.list.size())) {

bodyNodes.add(bodyConv.convert());

}

bodyNodes.get(bodyNodes.size() - 1).setIsTail();

// finish creating LambdaNode...We get the last element in the list of nodes of lambda and call setIsTail. With that, Mumbler will start the tail call flow whenever it encounters a function call in a tail position, even one embedded inside an if.

Conclusion

Truffle is really starting to show it’s capabilities. Tail call optimization may have been a little more complicated than I had originally planned, but the dispatch cache is something that any non-trivial language would have to implement. I’m more suprised Mumbler was able to work without it. Adding arbitrary precision numbers was a cakewalk. I didn’t expect the fallback from long to BigInteger would require so little code. I’m wondering how much effort it would take to add a full number stack with floats—ooh, or even rationals!

At this point, you can almost use Mumbler to write Real Code®. It probably needs strings and some more builtin functions. It could probably use the ability to create and call Java objects… stay tuned.

Update: Some Benchmark Numbers

I neglected to show how tail call optimization has affected the speed of Mumbler. First, though, keep in mind the goal wasn’t to make Mumbler faster, but to allow code like this.

(define countdown

(lambda (n)

(if (< n 1)

0

(countdown (- n 1)))))This is obviously a contrived example since countdown doesn’t do anything except heat up your computer and return 0, but without tail call optimization this function would eventually throw an exception. That thankfully won’t happen anymore, and with arbitrary precision numbers you can heat up your CPU all you want!

Having said that, how did TCO affect execution speed? Well, I created a benchmark that does basically the same as the example above except it breaks up the execution into smaller recursive function calls so it won’t throw an exception on the non-TCO version of Mumbler. That way we can directly compare TCO-Mumbler with non-TCO-Mumbler.

Here’s what I get with the non-optimized version of Mumbler. (Median after 5 runs).

mumbler (no TCO)

======================

('computation-time 410)Not so great. How about after I add all that TCO goodness?

mumbler (TCO)

==================

('computation-time 7)That’s a helluva drop. I wouldn’t expect such a drop since the same amount of work is being done, and Truffle was already optimizing our function calls in the non-TCO version. I think this is mainly due to a bug that was fixed while implementing TCO that allows further optimizations.

If we run the non-TCO version but with the bug fix what do we get?

mumbler (no TCO, bug fixed)

==================

('computation-time 229)Well it certainly helped, but it didn’t get near 7ms. It looks like Graal can make some excellent optimizations for control flow exceptions that remove a lot of the overhead of function calls and exception throwing. Bravo.